Crawling through pipes

- Sumit Basu

- Jan 4

- 6 min read

Updated: Jan 5

Millions of kilometres of pipelines carrying oil, gas and water criss-cross the face of the earth. Making sure that they are in good health requires robots that can crawl through their insides and check if the inner walls have defects. Prof. Bishakh Bhattacharya and his team have a low-cost solution. Its a PIG.

If you are used to waiting on a railway platform, you may have seen the man who goes around with something that looks like a metal rod, randomly picking wheels of a standing train and hitting them with it. The rod that he goes around with is called a wheeltapper’s hammer. The practice dates back many years and is essentially the simplest and possibly crudest example of what, in modern engineering parlance, is known as non-destructive testing (NDT). The man listens carefully to the sound emitted when he taps a wheel --- intact wheels ring like a bell, and cracked ones apparently give out a flatter sound. He is, in an error-prone but quick way, trying to detect the presence of cracks that may not yet be visible on the surface of the wheel.

Engineers today rely on much more robust tools when searching for cracks or defects hidden within large structures. Hidden defects are harmless if they do not increase in size over time, but if they do, they may reach a critical size at which they start growing catastrophically. Modern NDT techniques aim to detect as small a defect as possible and assess whether it has the potential to reach criticality under, for example, a sudden overload. In this context, defects in pipes pose a unique problem.

Millions of kilometres of pipelines carrying water, gas and oil at high pressure are crisscrossing the face of the earth today. A defect on the inside wall of a pipe is virtually undetectable till it gnaws through the pipe wall thickness and causes a visible leak. Given the right conditions, it may gnaw across the wall thickness and propagate along its length simultaneously. Both scenarios have resulted in accidents with a large number of fatalities. In 2014, leaking gas from an 18-inch diameter pipeline owned by GAIL caused a devastating fire in the East Godavari district of Andhra Pradesh, killing more than 20 people. The San Bruno pipeline accident in 2010 killed eight people when a long stretch of a 30-inch diameter gas pipeline literally unzipped along a faulty weld.

Pipe crawling PIGs

The inside walls of a freshly installed pipeline are pretty smooth. So where do the defects come from? Corrosion is a leading cause of deposits and metal loss on the inside. But construction defects, rough seas, and earthquakes can also contribute. To know the size and exact location of these defects, in-line inspection tools are often used. These tools essentially involve a robot crawling through the inside of a pipe, which uses one of several available methods to scan for possible defects. This robot is called a “pipeline inspection gauge” or PIG. So, the process of crawling through a pipeline has acquired the name “pigging”.

The most common method used by the PIGs is magnetic flux leakage (MFL), where a Hall sensor detects the distortion of a local magnetic field caused by a defect. Optical and ultrasonic waves are also used. Even newer techniques use ultrasonic waves triggered by Lorentz forces. Robots equipped with cameras and sophisticated image processing tools are also employed. Each method works well in particular conditions --- magnetic flux leakage requires ferromagnetic pipe walls, while ultrasonic ones work better for liquid-carrying pipes. These sophisticated methods do not come cheap—professional companies specialising in pigging charge as high as $100 for a kilometre of pipeline.

For over a decade, the Smart Materials and Structures Laboratory (SMSS) at IIT Kanpur, led by Prof. Bishakh Bhattacharya, has been working on developing a cheaper method. Finally, they now have a patented technology that will cost a fifth of what other companies charge, has already been adopted by GAIL and, most importantly, relies on ingenious use of simple concepts from mechanics to detect internal defects in pipes.

The PIG and speed control

Consider the robot first. The PIG consists of different modules connected through articulated joints, which allow the entire assembly to travel easily around pipe bends. Two of these modules, namely, the speed control unit and a module for defect detection, are essential. If required, modules for detecting defects through more than one method can be attached to the system. The entire system fits snugly on wheels in the interior of the pipeline and is propelled forward by the fluid pressure, without causing undue obstruction to the fluid flow.

For reliable detection of defects, the robot must move at a constant speed not more than 2-6 m/s. In most situations, the robot is much slower. However, in highly pressurised gas pipelines, the robot will accelerate and reach undesirably high speeds. This is where the speed control unit comes in. Most commercially available PIGs use an electronic speed control system where the amount of flow that bypasses the robot is actively controlled based on the pressure differential across the device.

On the other hand, the speed control system designed by the SMSS lab utilises frictional forces to maintain a constant speed for the unit. Whenever the wheels start rotating faster than they should, a brake unit generates high pressure that is, in turn, applied to the wheels as an additional normal force. The increase in normal force increases the frictional force immediately and slows the wheel down. The slowing down of the wheels instantaneously affects the hydraulic pressure in the brake cylinder, completing the closed-loop mechanical control system. This speed governor is robust and very cost-effective.

Detecting defects with bimorphs and cantilevers

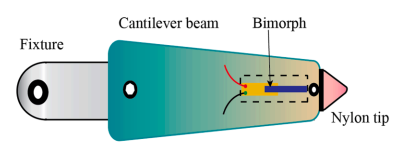

The defect detection module features a rotating disc with four innocuous-looking strips, evenly spaced along its circumference, protruding from it. Look closely, and you will see that these strips are tiny canilever beams with a slight taper and a triangular nylon tip attached. Pasted on the cantilever is another, even smaller, thin piezoelectric strip.

Piezoelectric materials produce electrical energy when mechanically deformed and vice versa. However, the attached strip consists of two stacked piezo strips, with electrodes located between them, as well as at the bottom and top. The piezo strips are approximately a tenth of a millimetre in thickness, made of ceramics, and the assembly costs around $4.

This is the well-known bimorph in a parallel arrangement, particularly suited to sense bending strains. When the cantilever beam bends, the piezo bimorph strip also bends, with one side undergoing tension and the other compression. The bimorph has two output leads—one from the electrode in the middle and one from the top and bottom electrodes, which are shorted. Also, the two piezo strips are poled in opposite directions. All this taken together ensures a stronger voltage signal (compared to a single piezo strip with two electrodes) when the cantilever bends.

As the PIG moves through the pipe, the cantilever, with its soft tip, presses lightly on the inner wall. If the pipe is smooth, the signal from the bimorph is small. However, as soon as the tip encounters a defect, the beam undergoes flexural vibrations, and the bimorph generates a voltage signal that carries the signature of the defect it has encountered.

Of course, the signals generated by the bimorph needs to be transmitted back to the users outside. Wireless receivers and transmitters mounted on the defect detection unit handle that. Odometers precisely record the position and speed of the PIG. Battery-powered units ensure that the rotating disc carrying the cantilevers operates for at least 10 hours.

The entire technology of the bimorph-based PIG, designed by the SMSS, has been transferred to GAIL. Unknownst to you, and of course unseen, several of these robots might be crawling through their gas pipelines looking for signs of internal corrosion as you read this article.

Further Reads:

Agarwal, V., Harutoshi, O., Kentarou, N., & Bhattacharya, B., Inspection of pipe inner surface using advanced pipe crawler robot with PVDF sensor based rotating probe. Sensors & Transducers, Volume 127, 2011, 45-55.

Santhakumar Sampath, Kanhaiya Lal Chaurasiya, Pouria Aryan, Bishakh Bhattacharya, An innovative approach towards defect detection and localization in gas pipelines using integrated in-line inspection methods, Journal of Natural Gas Science and Engineering, Volume 90, 2021,103933, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jngse.2021.103933.

Taha Sheikh, Santhakumar Sampath, Bishakh Bhattacharya, Bimorph sensor based in-line inspection method for corrosion defect detection in natural gas pipelines, Sensors and Actuators A: Physical, Volume 347, 2022, 113940, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sna.2022.113940.

Comments